Writing Samples

This article originally appeared in the February 1986 issue of Writer's Digest. The following introduction appeared with the story when it was reprinted in the book Just Open A Vein in 1987.

INTRODUCTION

by Bill Brohaugh

Editor, Writer's Digest

When Tim Perrin delivered the profile of Ray Bradbury we had assigned him to write, he wrote in his cover letter, “Please like this. It’s the best thing I’ve ever written.”

That would have been a boast had it not been true. And what Tim was recognizing in his piece was not the way he had written it, but the why of the way he had written it. It was a piece of writing celebrating how he had come to writing in the first place.

At Writer's Digest, we publish few profiles that opening place the subject on a pedestal, which this article clearly and unabashedly does. But in this case, I had a feeling that WD readers would respect the pedestal, welcome it even, because of how Ray Bradbury's writing must have touched them at some point of their careers. I had that feeling, I admit, because I knew how Bradbury's writing -- particularly the exhilarating Dandelion Wine -- had touched me. The letters we received after publish this in our February 1986 issue proved that my feeling was right.

Something else had proven that to me long before we went to press with that issue, though. It's a story I often tell, so bear with me if you've heard it before:

When Tim submitted the story to us, he also sent a copy to Bradbury. Bradbury, who was about to write an original article for us, called me soon after. “Have you read this article?” he asked me.

“Yes.”

“What did you think of it?”

“I liked it very much.”

“So did I. Why don't you run this instead of something written by me?”

“Actually, I don't see much problem in running both,” I said.

“Oh, OK then. I just didn't want to get in the way of this fine young writer.”

Mr. Bradbury, I am now even prouder to claim that I, too, am one of your children.”

* * *

Ray Bradbury is a wimp. That's not my word; it's his. I called him a nerd. It went like this:

Q: If I can use the term, I have the feeling you were a nerd.

A: [Laughs.] A wimp.

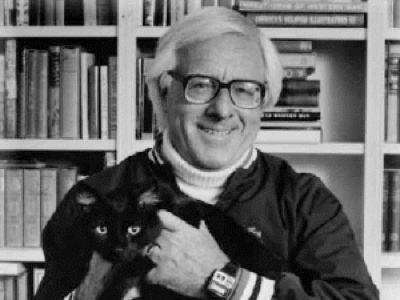

He's sixty-six years old, wears glasses as thick as Mr. T's forearm, need to lose thirty pounds, and admits to hating pain, being poor at sports, and being a favorite target of bullies in his childhood. He has lived more than fifty years in Los Angeles, where they build drive-in churches, for heaven's sake, and he can't drive. He sent entire cities to Mars more than twenty years before man took his first steps on the moon, yet will spend four days on a train rather than fly to New York.

In other words, a wimp.

So why, I thought, am I sitting in his office crying?

Perhaps it was because this is also the man who put the words in the mouth of Captain Ahab; who turned his hometown of Waukegan, Illinois, into “Green Town” and then transplanted it to Mars; who wrote so well even in his twenties that editors would tell him, “This story is too good for my magazine. I'm going to send it to Collier's or The New Yorker for you”; who created a family of vampires, fairies, and astral travelers in our midst, then set them wandering on a summer's evening; who brought us an illustrated man with tattoos that move, countless Martians, a twelve-year-old boy with a birth certificate proving he was forty-three, the Rocket Man, firemen who started fires rather than put them out, and a parrot who had memorized Hemingway's last, unwritten manuscript.

Mostly, though, I was crying because this is the man to whom I owe much of what I value in my life, the man who showed me what magic a writer could weave, what universes I could create. This is the man who gave me reasons to want to be a writer and I am crying because I can finally thank him for all that I owe him.

And he owes it all to Mr. Electrico.

The Labor Day weekend of 1932, when Bradbury was twelve, the Dill Brothers Combined Shows set up their tents on the outskirts of Waukegan. Mr. Electrico sat in a huge chair, his hair on end, his body glowing with “ten billion bolts of pure blue, sizzling power.” With a charged sword, he reached out and touched the boy Bradbury on both shoulders, then on the tip of his nose. “Live forever!” he cried.

The next day, on a pretense, your Ray came back and met Mr. Electrico in his uncharged state. A defrocked Presbyterian minister from Cairo, Illinois, Mr. Electrico showed Bradbury the mysteries of the carnival, introducing him to the strong man, the acrobats, the fat woman. Then he told the boy: “We've met before. You were my best friend in France and you died in my arms in the battle of the Ardennes forest. And here you are, born again, in a new body, with a new name. Welcome back!”

That was the stimulus Bradbury needed. He started writing. He wrote tales styled after those he read in Amazing Stories, yarns like “The World of Giant Ants.” “It was horrible stuff,” he says now. He ought to know. He still has all of those stories. He rarely throws anything away.

Then he discovered Jules Verne, H.G. Wells, and Edgar Allan Poe. He read everything by them he could find.

He read just about everything else he could find, too. In 1938, at the tail end of the Depression, he finished high school. But his family was on relief, so college was out of the question. “We had nothing. Nothing except the library, which was everything. I educated myself in the library by going there three, four times a week from the time I was eighteen until I was twenty-eight. I read everything. I went through all the short stories of all the major countries. I read all the major writers in the short story fields. I read all the major plays. I read all the major poetry. It doesn't take that much time. Two hours a day for ten years and you have read everything. Some of it you've read six or sever times.”

And he kept writing. Every day. Getting better. “I began to get really good after ten years. I started when I was twelve and when I was twenty-two I wrote a short story called ‘The Lake.’ It was about a real little girl I knew when I was eight or nine years old. She went into the lake and she never came out.

“That stayed in my mind until I was twenty-two and then I remembered. When I finished that story, I burst into tears and I knew that I had turned a corner in my life, that I had dredged up something. From that time on, I began to go deeper and deeper and deeper. All of the good, weird stories I’ve written are base don things I’ve dredged out of my subconscious. That’s the real stuff. Everything else is fake.”

Bradbury has been dredging like a harbor commission ever since. Anyone who claims to have read everything by him probably doesn’t know about half of it. There are the novels. The Martian Chronicles is really a collection of short stories. Fahrenheit 451 took nine days for the first draft. Dandelion Wine is a trip back to Bradbury’s childhood in Waukegan. His latest, Death is a Lonely Business, is a hard-boiled murder mystery about twenty years in the making. (“I had to wait for the character to come to me one at a time and ask to be in the book.”) Then there are the short stories, hundreds of them. There are the Mars stories, the Green Town stories, the Irish stories, the Mexican stories, and all those that don’t fit into any category. For years, he wrote one a week: first draft on Monday, final draft on Saturday, Sunday to refresh the muse. There are the screenplays: Moby Dick (John Huston directed Gregory Peck as Ahab and Bradbury earned an Academy Award nomination), It Came From Outer Space, The Beast from 20,000 Fathoms, episodes of the original Alfred Hitchock Presents and episodes of the revival of The Twilight Zone, adaptations of his own stories for HBO, and many others. There are the radio plays, the stage plays, the poetry, the essays, and even an opera (“Leviathan 99—Moby Dick in outer space”).

He writes first thing in the morning, just after waking. “I don’t need an alarm clock. My ideas wake me.” Characters come and speak to him, like the fire chief from Fahrenheit 451 who came to Bradbury one morning recently and said, “You never asked my why I burned books?”

“You’re right,” said Bradbury. “I never did ask. Why do you burn books?”

The fire chief told him and he added a scene to a novel he originally wrote more than thirty years ago.

“Before I go to sleep at night, I may think of what I might be doing the next day, but the important time is the waking-up time, when you are in and out of the subconscious. You post questions and they are answered in that half-dream state.

“When I was finishing my new novel, I put myself on that kind of emotional routine. I made a conscious effort to think about the novel before I went to sleep so that my subconscious would give me answers when I woke up. Then, when I was lying in bed in the morning, I would say: ‘What was it that I was working on yesterday in the novel? What is the emotional problem today?’ I wait for myself to get into an emotional state, not an intellectual state, then jump up and write it.” Revision, polish can come later. Now, he wants the guts.

“The trouble with a lot of people who try to write is they intellectualize about it. That comes after. The intellect is given to us by God to test things once they’re done, not to worry about thing ahead of time.”

“Bradbury learned to be relaxed about his work when he was in his early twenties and working as a street newspaper vendor for the old Los Angeles Herald-Express. “I did it three or four hours a day for about ten dollars a week. When I started, I was yelling, ‘Paper! Paper!’ After about six months, I was getting hoarse screaming the name of the goddamn paper. I experimented one day not yelling to see if it made any difference in the sales. There was no difference. I’d been yelling for nothing.

“That gave me my primary lesson. Don’t worry about things. Don’t push. Just do your work and you’ll survive. The important thing is to have a ball, to be joyful, to be loving, and to be explosive. Out of that comes everything and you grow. All you should worry about is whether you’re doing it every day and whether you’ve having fun with it. If you’re not having fun, find the reason. You may be doing something you shouldn’t be doing.”

If the writing is going well, Bradbury may stay at the typewriter in his basement office at home until he has completed several thousand words. Or he may take the morning’s work to his office in what has to be the last antediluvian building in downtown Beverly Hills, just a block from the ultra-chic shops of Rodeo Drive and a few doors up from the Ferrari dealer who sidelines in kiddie-sized sports cars.

His office is cluttered. If he were still a child, his mother would keep him in until he cleaned it. There are manuscripts, momentos, and just plain junk everywhere. A six-foot-tall pink stuffed Bullwinkle J. Moose graces a chair. A painting of Mr. Electrico covers one wall. He has autographed pictures of stars from when he used to hang around the gates of the studios during the thirties—Jean Harlow, George Burns, Gracie Allen. There’s a picture of the U.S. pavilion at the 1964 New York World’s Fair, which Bradbury helped design. And on the wall behind the couch is a poster-sized picture of Bradbury at the age of three. He has added a comic strip speech bubble that has the boy saying, “I remember you...I remember you...”

Bradbury does remember, too. Everything. “I remember being born. I remember having nightmares in my crib. I remember being suckled. I’m very fortunate in this way. But a lot of other people have this information, too. It’s never lost. The more you write, the more you word-associate, the more it rises to the surface. After awhile, you are dragging this series of word associations out and you’re not sure that you really remember these things, but you do.”

Confirmation of his memories came on a trip back home to Waukegan. He bumped into the town barber, a man who had boarded in the home of Bradbury’s grandparents in the summer of 1923, the summer of that picture on his office wall. “Your granddad had a wine press in the basement,” he told Bradbury. “He’s send you and your brother across the street with gunnysacks and you’d come back loaded with dandelions. You’d take them down to the basement and your grandfather would put them in the press and make dandelion wine.”

Dandelion wind. Until that moment, Bradbury had not known if he had just dreamed of making dandelion wine or if those memories had been real. “i wrote the book without knowing if it ever really happened, whether I was making it up or not. Here was the town barber telling me fifty years later that it really happened!”

Today an unopened bottle of dandelion wine sits on the corner of Bradbury’s desk.

Bradbury says the key to being a writer is not so much talent as rehearsal. “The gift is part; it’s there, but you have to rehearse it for many years. Doctors don’t suddenly become doctors overnight. They have something in there that comes out for some of them but it takes ten or fifteen years of rehearsal. Just write very day of your life. Read intensely. Then see what happens. Most of my friends who are put on that diet have very pleasant careers.”

His second tip: stay away from journalism schools. “That’s fatal. You don’t learn a goddamn thing. Journalism has nothing to do with writing. The great newspaper writers are not journalists, they are essay writers.

“In fact, going to college to become a writer is the worst thing you can do, because you are not following your own tastes. What you need to do is develop your strong bent, whatever it is. If you are going to be a mystery writer, be a mystery writer. If you are going to write science fiction, write science fiction. But colleges don’t understand that. They’re not going to encourage you to do something that you love.”

When he was starting out, even Bradbury had trouble doing what he wanted. Back in the forties, he was writing for Weird Tales. “They wanted me to do a conventional ghost story. I told them I couldn’t do that. I wanted to do the strangest things that popped into my head; the man who was afraid of the wind or the guy who was afraid of his skeleton.

“I had the same problem with the science fiction magazines. They were doing conventional, mechanical, technological pieces and many of them still are. I was writing human stories about little boys who want to grow up and become rocket men. What kind of science fiction story is that? It isn’t at all.”

Rather than being rejected, though, Bradbury’s stories changed the nature of the market. His horror stories, written for fifteen, twenty-five and thirty-five dollars for Weird Tales, are now gothic classics. The magazines that wouldn’t publish Bradbury’s new style of human science fiction dies and the entire genre adjusted to make room for it.

In fact, the man who is billed on his book covers as “the world’s greatest science fiction writer” is not really a science fiction writer at all. Editor Donald A. Wollheim said of his writing: “It has the form of science fiction, but in content there is no effort to implement the factual backgrounds. His Mars bears no relation to the astronomical planet. His stories are of people, real and honest and true in their understanding of human nature—but for his purposes the trappings of science fiction are sufficient—mere stage settings.”

Critic Willis E. McNelly said of Bradbury: “His themes... place his squarely in the middle of the mainstream of American life and tradition. His eyes are set firmly on the horizon-Frontier where dream father mission and action mirrors illusion. And if Bradbury’s eyes lift from the horizon to the stars, the act is merely an extension of the vision all Americans share.”

His writing, particularly the stories based in Green Town, have a nostalgic air, a harkening to a time that we perceive as simpler. Yet, McNelly called it a “nostalgia for the future” and Ray Bradbury, despite the homey, Midwestern, small-town settings of many of his stories, is definitely a city person with his eyes fixed on the next century. “We’re going to rebuild all the cities of American during the next twenty years. We’re on our way there now. All of this is due to the influence of people like Disney. He has taught the mayors of the world that their cities can be more human. They can have more gardens, more fountains, more places to sit. We are getting more interested in the quality of life. We’re getting interested in rebuilding our cities and rebuilding our small towns. Parts of L.A. are being rebuilt right now. They’re working on downtown San Diego. They’re spending a billion dollars to humanize that.”

Bradbury affection for Walt Disney was reciprocated. When the Disney people were designing the Epcot Center at Disney World in Florida, they called on Bradbury for ideas. And at Disneyland’s thirtieth anniversary celebrations, Bradbury was an honored guest.

His influence is long-term, touching several modern-day Disneys as well. For instance, in the 1960s, Bradbury spoke at a Southern California high school. Inspired by Bradbury’s enthusiasm for movies, one young student turn to a friend and said, “I’m going to be the greatest filmmaker there ever was.” Gary Kurtz went on to produce American Graffiti, Star Wars, The Empire Strikes Back and Dark Crystal.

Bradbury speaks of many of today’s creators as his “children” and some of them acknowledge it opening. “Are you still my papa?” Steven Spielberg asked Bradbury on their last meeting. “Yes,” was the reply. “I’m still your papa.”

“Do you have any idea of the number of lives you’ve changed?” I asked Bradbury.

“I have an idea it is quite a few.”

It was then that I realized why I was crying. “I am one of your children, too,” I said.

“I know,” he told me. “I can see it in your face.” And he stood up, came over to me and wrapped me in his arms. Not a wimp’s arms at all but a father’s arms, the arms of a man who has as many creative children as any author of his generation.

Thanks, Ray.

And thank you, Mr. Electrico.

Ray Bradbury’s Children

Published in: Writer’s Digest

February 1986