Writing Samples

In Canadian military history, the name Passchendale is one of the most important. The Passchendale action was merely part of the larger battle that took place around the town of Ypres, which had the unfortunate fate to become a place the Germans wanted and the allies decided to defend. In fact, there were three battles for the town. The first occurred in late October and November 1914. In the second, in April and May of 1915, the Germans tried out their new secret weapon, chlorine gas. After this attack failed, the Germans contented themselves with merely blowing the town to bits with constant bombardment.

But it was the third battle of Ypres that has come to be known simply as the battle of Passchendale. Unlike the others, this was launched by the allies. The British commander, General Haig, hoped to break through the German lines, though why he thought he could do so after three years of stalemate is beyond me. Nonetheless, in July, he started a 10-day bombardment of the German positions. So much for surprise. When the troops came out of their trenches, the German machine gunners were ready for them. Over the next three-and-a-half months, more than 310,000 allied troops were killed and wounded, more than 250,000 Germans. In the final push in early November, British and Canadian troops survived mustard gas attacks to take Passchendale ridge, General Haig declared victory, and everyone dug in for the winter. At its greatest, the advance had been about five miles.

More than 12,000 victims of the various battles in and around Ypres are buried at Tyne Cot War Cemetery in Passendale (the modern spelling), about eight kilometers northeast of Ypres. About 1,000 of them are Canadian, more than half of them unidentified. Another 35,000 names of men whose bodies were never found are inscribed on the marble walls of the cemetery. Below one panel, we found a note:

James Smith Graham:

We are sorry that life was taken from you so early and that we never

had the chance to know you.

From your grandchildren,

Hugh, Alison, and Jean.

It reminded me of the notes you see at the Vietnam Memorial in Washington.

The cemetery was built in this location because a first-aid station was set up in a cottage (the Tyne cottage) and they had to bury the bodies nearby. Today, the memorial is built around the cottage. You can still see one of the walls through a gap in the wall of the memorial.

There were several Royal Flying Corps pilots, just 18, lieutenants at that age, shot down over the battlefield.

One of the reasons I go to the cemeteries is to say that I remember and to say “hello” to the guys there. They died a long way from home and I’m sure there are many who have never had a visitor from home. I know they’re dead, but if there is an afterlife, and if they are watching us, I want them to know that even though I disagree with war, I recognize what they did and the sacrifice they made, and how they suffered, and in the long run, the life it bought for me.

(There were also two German buried there. I made sure to tell them hello as I expect they don’t get many visitors in this cemetery full of Brits, Canucks, Aussies and Kiwis.)

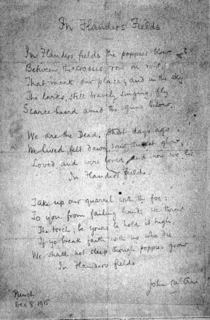

It was also at Ypres that Canadian field doctor John McCrae knocked off a few lines of poetry while he was sitting on the bumper of an ambulance. He didn't think much of them and he tossed the piece of paper away. But one of his friends picked it up and sent it to Punchwhich printed it--without a byline--on December 8, 1915. McRae's poem was printed at the bottom of page 468, right after an ad for "The Little Dentist.--Entire outfit, including minature Forceps, Gags, Gasbags, etc. Will keep an entire nursery happy for hours. Help baby with his teething. 5s 6d."

It was called "In Flanders Fields."

Today, in the museum at Ypres, there is a small glass display case devoted to McCrae and his poem. I particularly appreciated the fact that it included a "refutation" from artist Brody Neuenschwander who had tried to prepare a calligraphic interpretation of the poem but who had found himself unable to do so. "It was not difficult to make backgrounds that suggested the grayness of the Flemish skies," he wrote, "and the deeply depressing aspect of the mud and the death of the trenches. But everytime I placed the words of the poem over the background, I read the words, 'Take up our quarrel with the foe,' and I saw that it did not work.

"John McCrae's own handwritten copy of the poem has become an icon of the famous text. We see it, we know what it says, we accept it. But do we stop to ask what the poem actually says? Do we want to know why so many young men were so willing to follow their comrades to the front? Do we have any idea of the social and politcal pressures, propaganda and un-critical patriotic enthusiasm that allowed the leaders of the time to commit this vast slaughter?"

On the way home, my eye was caught by a sign not far from Dirk and Magda’s house that said “452 Sq. RCAF Memorial” and pointed down a little side road. We did a u-turn and turned down this short dead end. On the edge of the lawn of the farmhouse at the end of the road was a marble marker commemorating the crew of an RCAF Halifax that crashed nearby in 1944.

Memories of the war(s) are everywhere in this part of the world.

Passchendale

Posted on: The Coast Road Travel Blog

Sept 20, 2005