Writing Samples

In Canada, we talk about ourselves as a “multicultural” society and we hold little multicultural fairs every Canada Day. We all eat perogies and chicken tika masala. The local MP makes a speech about how tolerant we are and we pat ourselves on the back.

In Europe, they have to live tolerance on a day-to-day basis or they will start to kill each other again.

It’s that simple.

We were at a party on Saturday evening attended by about two dozen people. We counted at least a eleven native languages represented at the table: English, Dutch, Polish, Russian, Ukranian, Hebrew, Spanish, Arabic, Farsi, Swahili and Hindi. The guests had been born in Holland, Canada, the US, Surinam, Poland, Ukraine, Argentina, Iran, Tanzania and Egypt. There were atheists, Muslims, Hindus, Jews, and at least four colors of Christians – Catholic, Orthodox, Dutch Reform and Baptist.

Among the older attendees, one man had spent three years in hiding to escape the Holocaust; his son, a computer engineer; his daughter, a judge; and his three grandchildren would not have existed at all had he not survived. Another was Iranian-Kurdish-Jewish, a member of a double minority in a strongly Muslim-Persian country. He spoke Farsi, Kurdish, Spanish, Russian, and English, all of which he had learned of necessity in a life of adversity and challenge. He was married to a Jewish woman from Argentina. They now live near the Golan Heights in Israel, still in a world subject to war.

But most of us had been born since 1945. We were heirs to the legacy of peace our parents had left us. Some at the party were active in preserving that. In particular, one guest was a mediator for NATO working with nations to help them find ways to resolve their differences short of arms.

The phenomenon of modern Europe runs against all sense. Political units do not surrender power to a central authority unless they absolutely must. It took the United States three tries—the Articles of Confederation, the Constitution, and a vicious civil war—to settle the issue of just how much power the states had ceded to Washington. In Canada, Quebec keeps the debate in the daily headlines as it strives to maintain and even expand its powers. Yet this spring, ten countries were eagerly waiting in line to give up vital areas of sovereignty and join with 15 others in the European Union, a creature that defies logic. Just 14 years ago, political centrifugal force spun the Soviet Union into its constituent parts and again sparked ethnic bloodshed in the Balkans. But here were countries like Poland and Hungary saying, “Let us in!” Turkey is almost begging to get into the EU, asking what else it has to do to qualify.

This miracle, this marvel, is primarily the work of two former bitter enemies, France and Germany, who, after tearing each other to shreds twice in thirty years, realized they could not live through another war, one that would be even worse than the two that had just killed off two generations of their sons. So, they have been the driving forces behind the EU. In the face of resurgent nationalism, they have remained resolute and determined to make the EU work, despite their differences, which are many.

The new EU constitution failed to gain ratification earlier this year. I pray that will not stop the movement toward a united Europe. Like Quebec, I hope that they will keep asking the question until they get the answer they want.

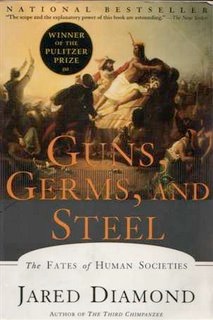

I just read Jared Diamond’s book Guns, Germs and Steel. It attempts the answer the simple question of why Eurasians have so much more wealth than Africans and Native Americans. Why did Cortez conquer the Aztecs and not Montezuma come to Spain and conquer Ferdinand and Isabella?

In the book, he talks about the evolution of human societies from simple bands, where everyone knows everyone else and is probably related to them, to tribes, where you still know everyone even though there are probably several hundred people in the tribe, to the larger chiefdoms, where the population becomes too large for you to know all your neighbors by name. That’s when dispute resolution starts to become a real problem. Diamond tells how in New Guinea, where he has done much of his research over the years, when two people who didn’t know each other met on the road, they would engage in a long dialogue discussing their ancestors and relatives in hopes of finding some relationship so that they did not have to fight and try to kill each other.

In Europe, today, they are working at finding those relationships, the ways in which we are all the same, instead of the ways in which we differ.

They don’t really have much of a choice.

Bosnia showed us just how quickly things can go down the crapper and just how long old prejudices can hang around.

But what I find really interesting, and more than a bit upsetting, is the blind spot I’ve noticed in some of the people I’ve met. They are marvelous folks, let me be clear, but more than once I have heard someone make a comment about how horrible Hitler was and decry the holocaust, yet not three sentences later, the same person will say something about “the damn Moroccans.”

Moroccan immigrants are the underclass in Holland and other parts of Europe. As with every immigrant group—even my group, the Irish, in their day—they are not wanted, ghettoized, and dishonored. But it scares me to hear such words from people who live within 80 kilometres of the deportation camp used to send thousands of Dutch Jews to their deaths at Auschwitz, Treblinka and Buchenwald.

We are all bigots at some level. I know I’ve got my blind spots. At least, I assume I do. They wouldn’t be blind spots if I knew about them. But I try to be open when someone points one out and not to defend for too long.

But I have friends who lost their families in the camps. I expect that every one of us knows several Jewish people, and I can just about guarantee that they lost dozens of family members in the Holocaust. It was not long ago and far away. It wasn't just Germany in the 40s. It was Armenia in 1915. It was the Soviet Union in the 30s. It was China in the 50s. It was Cambodia in 1975. It was Rwanda in 1994. It was Bosnia in 1995. It was right here. It was yesterday, and it will be tomorrow.

And “they” didn’t do it. Good, upstanding, right-thinking people who "knew" they were doing the "right" thing—people just like us—did it.

And it all starts with saying, “Those damn Jews,” "Those damn Tutsis," "Those damn Bosnians."

"Those damn Moroccans."

Those Damn Moroccans

Posted on: The Coast Road Travel Blog

Sept 14, 2005